By definition, collaboration finds strength in cooperation and the establishment of a shared vision. In practice, however, it requires a certain level of relinquishment. Of ego, of control, and, in some cases, of intent. Compromise is a word that comes to mind, which also implies a kind of sacrifice. That’s why the best collaborations require evolution, an openness to change. Not only creatively in terms of execution, but also cognitively in regards to conception. Ideas must remain fluid and differences resolved in order to arrive at something (hopefully) better and new.

It can be a delicate balance, and some artists come to it easier and more naturally than others. In the case of Atlanta’s Lowtown, the sharing of ideas and surrendering of egos has always been something of a given. Led by the songwriting prowess of guitarist/vocalists Beaux Neal and John Pierce, the band’s blend of dark doomsday country and fiery punk blues is the result of unshakeable mutual trust and endless experimentation. “We collaborate constantly and feel very comfortable with that at this point,” says Neal. “We have our differences in taste and opinion sometimes, of course, but all in all, it’s been seamless from the beginning.”

Still, when the group decided to partner with filmmaker, musician, and Immersive Atlanta co-founder Luciano Giarrano to create a new music video, there were doubts that needed to be confronted. Part of that uneasiness stemmed from the way the partnership was haphazardly formed. After attending a Lowtown show at 529 last fall, Giarrano was speaking with drummer Russell Rockwell when Rockwell unexpectedly floated the idea to Neal. Unfazed, Neal agreed to the collaboration without seeing Giarrano’s work or realizing that, despite several years of teaching and working in film, he had never created a music video.

Fortunately, subsequent planning sessions helped ease their concerns. Over time, Neal and Pierce came to appreciate Giarrano’s professionalism and willingness to ask tough questions. Giarrano, meanwhile, liked the pair’s motivation and willingness to think outside the box. The biggest challenge, as it turned out, was settling on a song to collaborate on. Initially, the band wanted to cut visuals for “Easy Drinker,” the pensive, world-weary ballad from the band’s new LP, God’s Chicken. But after a month of trading ideas, nothing compelling emerged and the project fizzled out.

It would be several weeks before Neal and Pierce would decide to engage Giarrano again. This time, they suggested taking a stab at the stormy mid-album stomper “Tuxedo in Blue” and included an outline of a possible creative concept drawn up by Pierce. With this outline as inspiration, the collaboration hit full swing. Sketches of ideas began to fly back and forth and slowly a shared vision was hammered into shape.

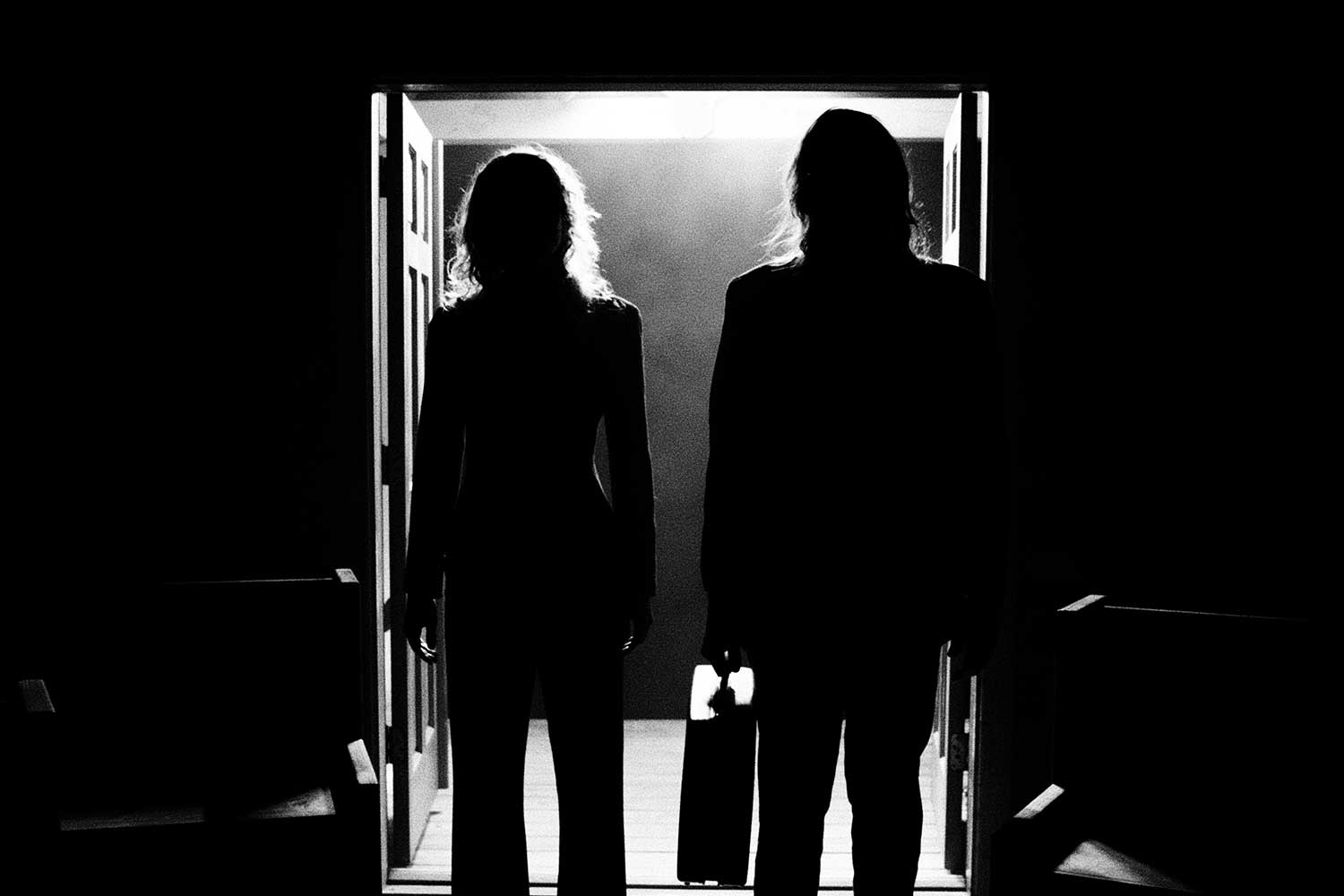

Built on a classic black and white noir framework, the video for “Tuxedo in Blue” is a visual tour-de-force. In it, Neal and Pierce play a pair of soul-stealing con artists hell-bent on fleecing the meek and easily exploited. Through a series of vignettes both haunting and hilarious, we watch them commit their crimes utilizing everything from sexual temptation to cult-preacher hucksterism. Whatever it takes to get the mark to sign on the dotted line.

Given the song’s themes of self-discovery and personal doubt, the video makes for a fascinating study on identity and the human tendency to seek approval and acceptance from outside forces. Beneath its gritty, transgressive exterior is a sharp examination of how vulnerability can lead to putting one’s faith in people or institutions that can be desperate and manipulative. Through it all, Giarrano remains in constant command, peppering the video with arresting images and clever narrative devices that keep the viewer engaged. Considering the project’s tiny budget, the finished product is a testament to his ingenuity and eye for detail. But most of all, “Tuxedo in Blue” is a credit to the power of collective trust and the spirit of creative cooperation.

Watch/listen above.

Recently, we spoke with Neal, Pierce, and Giarrano about the making of the video and the nature of their collaboration. The following conversation has been edited for clarity.

Why did you all agree to collaborate on a music video?

Beaux Neal: I trust in John’s ideas and I’m grateful for his trust in mine, so when it was time to make a music video for one of his songs I was excited to help bring his vision to life and participate in any way that made sense.

When I first met Luci he told me a little bit about his background in film, and I had a very real sense that he was the real deal. Come to find out he was the real deal, and more. Professional, imaginative, knowledgeable. Even in our earliest brainstorming sessions he posed interesting possibilities, asked difficult questions, and generally put so much care and thought into the budding project. I’ve come to see the way Luci works and collaborates with others and I value his commitment to working with other people to make things. I see that in all of us, really.

Luciano Giarrano: They were making good music and they were willing. I wasn’t fully committed until we grabbed a few drinks at Righteous Room and connected personally outside of a late-night casual comment. Hannah was motivated and professional and John seemed open to any possibility. It’s the things you’re looking for when considering committing to months of work with anyone.

We actually started with another song off the record but it wasn’t quite clicking. We didn’t have a strong idea for it. All we knew is that we didn’t want the band lip-syncing or playing on screen. So we scrapped that and sat on the collab for a bit. After a month or so Hannah reached back out and threw me another song off the album, this time with an outline of an idea from John, who wrote the song.

What expectations did you all have going in and how did those evolve along the way?

JP: I don’t like to go into collaborations with expectations. I feel that any artist I work with should have the availability to shine and I don’t ever want to inhibit anyone’s creativity.

BN: I partially expected the timeline to go as expected, which is insane. [It] was psychotic in terms of expecting to get that much footage in as many different scenes as we wanted to in such a short time period with basically no budget. We made what could be and is basically a feature-length film. I’m very proud of us for pulling together and playing multiple roles and also taking breathers and doing the best that we could with what we had access to. I think that I learned Luci’s filming style over the course of the shoots and that was always a wonderful surprise.

Why did you land on “Tuxedo in Blue”?

BN: As [bassist] Aidan [Burns] would say, it is a 100% USDA-certified banger, and was an early choice for a single off the album. The single that never was.

John, what was your original interpretation of the song’s visuals? How much did they spawn from the song’s original meaning?

JP: I don’t really know. I guess the song kind of talks about coming into your own self, but it also deals with how I act confident but in reality, I’m very self-conscious. I love cults and I’m very interested in theology. [I’ve] listened to a lot of podcasts about the famous cults—I was really into Waco and the Ranch Davidians. I also liked the idea of a door-to-door soul collector. I thought it was funny imagery to have like Jehovah’s Witnesses… it’s funny how people intrude on other people’s lives to spread the good word.

BN: Initially, John dreamed big, and then Luci and I trimmed the fat. You have to have both to make something happen. I’m no expert, but I’ve been involved in a couple of DIY film experiences at this point and it’s generally a lot more work than you can imagine. In that vein I think it’s important to be realistic where you can, and also use your resources. The scenes John initially imagined involved a lot more people, and I’m so grateful we were able to corral our friends into the seminar scene.

I’m also thrilled that we landed on the tiny chapel where John and I recorded a dirge in early 2019 rather than trying to finagle some church in town to film our slightly sacrilegious music video or trying to baptize/fake drown ourselves in the cursed and bacteria-laden Chattahoochee. In short, the idea came together by the three of us allowing it to shift over time as the narrative sharpened shoot by shoot. I think the video is so wonderful in that you pick up on new details with every watch… like any good film. And I also think that reflects the idea’s evolution.

LG: John’s outline was a great starting point. We just had to tie some things together. Somewhere in it he had written the phrase “soul heist.” It called to mind old noir thrillers—The Killing, Touch of Evil, The Third Man, mixed with gothic or supernatural horror like Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Rosemary’s Baby, and maybe a sprinkle of Scanners. Stills from the 1945 movie Detour ended up being a lot of what was on my mood board. That set the tone and the style ended up solving our production limitations. We didn’t have much of a budget which meant I was pretty much going to be the crew with a production assistant here and there. I’m used to working that way but it just meant we had to be creative with our choices to lessen the technical burden.

How did you happen upon the imagery for the video?

LG: Once noir was on the table we talked about committing to it with a 4:3 aspect. This meant less set dec to worry about or the chance to overthink lighting on the edges of a wider frame. It also meant with stylized lighting we could veer away from realism as much as we wanted, which opened up fun stuff like old-school camera tricks, rear projection driving, montages, etc. After that, we started to look for cool locations and we were off.

To be honest I didn’t know what the song was about and still don’t. I just worked off John’s outline and interpreted it myself, came up with my take on the visuals, and we never really discussed it. You’ll have to ask John what he meant. I came up with my own meaning.

JP: I still don’t know what I mean. I don’t like telling people what I mean, it’s up to them.

LG: For me, the whispering of Hannah’s character to the victims—the image of which was in John’s original outline—represented the ease of being manipulated when one is already lulled to catatonia by self-inflicted laziness, apathy, and dispassion. The seminar scene pulled triple duty representing get-rich-quick schemes, vapid motivational speakers, and televangelists preying on people. Our desperation for hope and belief in the pursuit of understanding and meaning. To feel purpose. Money and materialism of course being a subrogate for purpose. Typical. Cynical. BS. But super fun as a basis for cool imagery! And maybe someone will find it interesting.

How would you compare the process of songwriting to the process of creating the music video?

JP: I’m definitely more inclined to songwriting. The hardest part was acting without feeling like a fucking idiot, the most fulfilling part was seeing it all come together.

BN: It’s the same thing but longer and more involved, with more moving parts and grit required to reach some kind of a finished product.

What or who are you most inspired by in terms of production?

LG: What’s that Quincy Jones quote? “The only music I don’t like is bad music.” Same with film for me. For this video specifically, we landed on noir for inspiration, in part to solve budget and logistical issues but it’s a genre I nonetheless love. What inspires me about production in general is interminable problem-solving and making good shit with good people.

BN: Would you ever consider a longer cut of the video for a short film (laughs)?

LG: Yeah def. I overshot. I was having fun. I like being in charge and, on occasion, benevolent.

Lowtown will perform on Thurs., Jul. 13 at Innerspace alongside Frank & the Hurricanes, Nash Hamilton and the C.H.O, and the Pierres. Doors open at 8 pm. Admission is $10.

More Info

Bandcamp: lowtownofatlanta.bandcamp.com

Instagram: @__lowtown